The e-book link is https://skydrive.live.com/redir?resid=87BFF6A8F1E1FE91!247 . The format will allow viewing on the smaller devices such as Kindle and Kobo ereaders, but the maps included really require the larger screens of the I-Pad, notebook or laptop.

Cover of the Book Showing William Odgers VC, Taken in New Zealand 1860

The Photograph of William is an Enlargement From One Assembled by W F Gordon, By Kind Permission of Museum of New Zealand, Te PaPa Tongarewa (O.013443/01)

Simplified Dunsford-Stoddon-Odgers Tree

The Ashtor House Restaurant (1901) Located at Top of Ferry Slipway

Auntie Jose Family at Ashtor House

Auntie Jose on Her 100th Birthday With Ginny

She Loved Dogs

About Saltash

It was to the Waterside that Drake, Hawkins and their associates brought their booty for safe storage in Trematon Castle prior to transport to London and the Tower. For me, the area retains a good deal of the history given it by these adventurers.

Tamar St. itself is really the setting for this story. Up until WWII it was known as 'Pickle Cockle Alley' for the sale of shellfish from its shop fronts. At one time there were 21 of these retailers in the one street, and my great-grandma Adelaide was one*.

Aerial Shot of Saltash Showing the Location of the Old Waterside, After its Destruction

With Thanks to Cyberheritage

View from the River Tamar of Old Waterside from 'Wheatsheaf' to 'Union'

The Old Tamar Street Towards the Bridge

And the Other Way

My Great-Grandmother Adelaide outside 24 Tamar Street, Early 1900's

+cropped.jpg)

With Thanks to Cousin, Norman Ash

James Stoddon Headstone Records Death of 42 yr Old Wife, 2 Infants, 2 Young Daughters

John Dunsford 1800-1890, Patriarch of the Waterside

With Thanks to My Aunt, Margaret Howatson nee Craven

John Dunsford Family Headstone at St Stephens

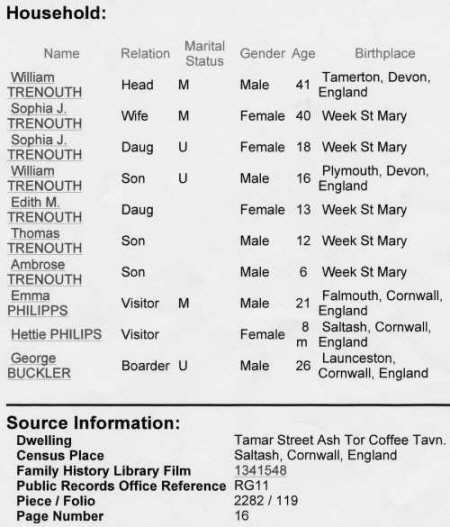

A Section of the Marriage Certificate for Jane Dunsford and Isaac Stoddon

The Matrimonial Causes Act 1857

With Thanks to Channel 4

Jane Odgers' Virtual Headstone

Life in the Mid-Victorian Navy

To begin with, it is easy to see why the Navy were keen to recruit young boys into the service. They could be as young as 12 or 13, were often orphans or motherless, and were soon adept at the tasks on deck or in the rigging. There is nothing like starting at an early age to develop the particular physique required for sailoring. Incidentally, these young boys were safe from violation; most of the crew disapproved of homosexuality, as did society, and the Navy punished any evidence of it with the ultimate severity, hanging. In fact, physical punishment for any misdemenour which affected the safety or smooth operation of the ship, including drunkeness, was severe and public.

The introduction of Continuous Service Engagement (CSE) allowed the Navy to plan ahead for its envisioned crew requirements and to a certain extent to dispense with the need for impressment from the merchant service when war threatened. Starting at such a young age, the crew soon became highly skilled in their work. When trained they would sign up for 10 years service and often leave with a pension in their twenties to pursue an alternative life.

At sea the essence of efficient sailing, fighting, and hygiene, was teamwork. The crew were divided into groups for watches, or messes for housekeeping activities like the preparation of food, cleaning dishes and cleaning 'heads'. The availability of food and its quality was much better than is commonly thought. In a week each sailor could expect 7lb biscuit, 7 gallons beer, 5lb beef, 3lb pork, 2lb pease, 4lb oats, 8oz butter and 12 oz cheese; they were therefore eating rather well compared to life ashore. The immediate surroundings of the ship solved the shore problem of human waste disposal, and that and the isolation from the general population for long periods greatly reduced the risk of disease. Scurvy was no longer a threat to the crew, once the efficacy of lemon juice and, later, lime juice was established. Only on certain duties was sickness a problem. The African squadrons, for example, who were often exposed to various fevers, gave the ship's surgeons something to investigate.

As we shall be able to deduce from the various ships in which our sailors served over the period 1837-1865, the Royal Navy was then in a crucial state of flux with regard to what kind of ship to build; warship, frigate, sloop etc. What kind of propulsion to include; sail, screw, paddle or a combination, or, later, of what material to construct the vessel. In fact they frequently held trials with differing designs to try to determine the most effective ship in any given set of circumstances.

Of course, the answer was complicated by the nature of the duty any ship was required to take. It was no use sending a wooden three-deck warship to intercept slave traders in the environs of the Zambesi, or to navigate the Canton river in the China wars.

For this reason we shall describe the nature of the ship in which our sailors served so that the reader can determine for himself whether they suited the particular circumstance(s).

One type of boat evolved during this period which was to have an enormous impact on the Royal Navy, and its enemies, throughout the second half of the 19th century.

The early ones were much lighter than conventional paddle sloops, for example, at 200-300 tons. They were about 100 ft in length, with a beam of 20-25 ft, and screw propelled. They initially carried 2-3 68-pounder guns! The main requirement of the design was the ability to float in only 7' of water.

None of our heroes served in one, but it was used with great success in the Crimea, the Baltic and the China second war.

It was the gunboat.

The Vulture landing Dispatches at Danzig, 1843

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Seamen From HMS Vulture Under Attack at Halkokari June 7 1854 - Vladimir Swertschkoff Lithograph

http://www.port.of.kokkola.fi/historia/english/barken_koko_eng.html

English Sailors & French Soldiers. A Dance on Board HMS Vulture Aug 7 1854 (Caricature)

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Distribution of Naval Vessels for Attack on Sveaborg, HMS Vulture Bottom Centre - W L Clowes

http://www.pdavis.nl/Baltic9.htm

The Bombardment of Sveaborg - A Chromolithograph Based on a Drawing by M. Beerger

http://virtual.finland.fi/netcomm/news/showarticle.asp?intNWSAID=25997

HMS Niger at Vera Cruz

London Illustrated News

Canton and Defensive Forts Dec. 1857

http://www.pdavis.nl/China2.htm

The First Taranaki War

Naturally enough, the disputes which started off the series of battles were generally about land.

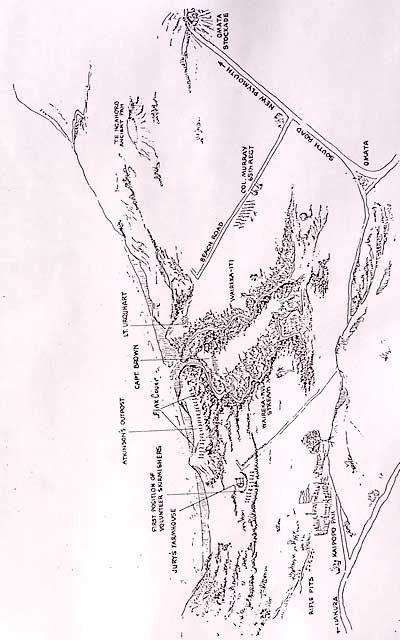

Here we are really only concerned with two of the 'battles'; that at the 'L' Pah (Te Kohia) which wasn't really a battle but perhaps an attempt at extermination, and Waireka, where the men from the Niger were engaged at Kaipopo Pah. In order to make the details of the battles more readable, two maps and a drawing are given here. The first gives the locations of the battles near New Plymouth, the second a detailed sketch of the Waireka field of battle, and the drawing gives the perspective of the Kaipopo Pah relative to the river basin. These should be used with the text describing the movements of the various groups involved in the battle.

Finally, it has to be said that there is inevitably controversy surrounding the outcomes of these battles. Was it a victory or a loss? Did these terms have the same meaning for the antagonists? How many died? Did the Maori run or was that a tactic etc etc.

Surprisingly, I have found there to be little disagreement over the descriptions of the battles themselves. I have used as principal source Captain's Cracroft's Journal, written in 1862, because I happen to believe it to be a reliable account, and it generally fitted in with less detailed descriptions.

Extreme views from either side have generally subsided with the years and it is important to remember that, here, we are telling a story about an ordinary hero, not a politician or Government appointee, but a man who was simply doing his duty.

As a footnote, in its 1996 report to the Government on Taranaki land claims, the Waitangi Tribunal observed that the war was begun by the Government, which had been the aggressor and unlawful in its actions in launching an attack by its armed forces. An opinion sought by the tribunal from a senior constitutional lawyer stated that the Governor, Thomas Gore Brown and certain officers were liable for criminal and civil charges for their actions.

It is also worth noting that Captain Cracroft's journal, published in 1862, is highly critical of Colonel Gold's (the British field Commander) handling of both the initial situation with the Maori and the subsequent movements of the British troops and the volunteers.

Map of Taranaki Region Showing First Taranaki War 1860-61 Battle Sites

'MAORI WARS', from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966.

Drawing of Waireka Battlefield. The Blue Jackets Approached the Pah Along the South Road to Omata

Sketched by Murray Moorhead

Drawing of Waireka Battle from Perspective of the Jury Farmhouse Showing Elevation of Kaipopo Pah

Drawing by A H Messenger

William Odgers Climbing the Stockade at Kaipopo Pa - An Artist's Impression By Harry Payne (1900)

With Thanks to Ron Lambert of Pure Ariki, Taranaki Museum

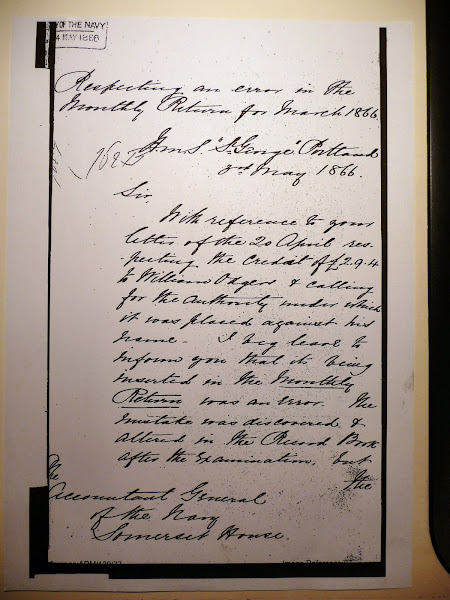

The Accountant General's Letter Admitting Error of £2-9-4 Overpayment to Odgers

William Odgers' headstone at St Stephens

Mural on the Wall of the Union Inn with William Odgers on the Right

Suppression of the Slave Trade

1787 was the the year the popular movement against the British slave trade suddenly took off. Although there were no slaves in Britain itself, the vast majority of its people accepted slavery in the British West Indies as perfectly normal.

At the end of the 18th century Britain dominated the trade, with more than a hundred slave ships leaving Liverpool, Bristol, and London each year as the slave-based economy of the West Indies thrived.

How did the abolitionists turn this situation around? Well we can't answer that question here, but a read of the Hugh Thomas book 'The Slave Trade - The History of the Atlantic Trade' might help.

Well the ordinary heroes were the Quakers; the first religious group to protest and the providers of most of the movement's PR and financial support.

Miraculously, the Act was passed despite the many petitions against; from 1 May 1807, the trade was illegal. The penalties were also severe; £100 for each slave found on board and confiscation of the ship.

Lord Grenville, the Prime Minister, believing that Britain was 'unrivalled on the ocean' was of the opinion that the trade could swiftly be brought to an end. British arrogance and aggressive pleasure in interfering in the commercial activity of other countries eventually led the way to abolition but it was an almost impossible task without the cooperation of the other nations involved in letting the British board their vessels.

Service in the West Africa Squadron was full of risk and posed a constant threat to health from the many fevers available. The mortality rate was about five times that in home waters.

There was a significant development when new treaties allowed that circumstantial evidence of slaving on ships, chains, cells, extra storage etc, was sufficient to prove the illegal trade. This vastly improved the British success rate and, in time, led other countries, even France, to allow their ships to be searched.

However, total success in the Atlantic took nearly 60 years including 15 years of Isaac Stoddon's life.

HMS Ringdove, Sister Ship to HMS Sappho - Isaac Sailed in Both These Sloops

HMS San Josef in Her Pomp

http://www.centreboard.net/armed_forces/royal_navy/gt_falcon.htm

Captain W. H. Hall, in HMS Hecla, Towing the Penelope at Bomarsund in Baltic War

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Report from Commodore Jones of HMS Penelope to 2nd Secretary of Admiralty 3rd March 1845

Commodore Jones to Captain Hamilton.

"Penelope," Ascension, April 5, 1845.

I HAVE the honour to report my arrival at this island on the 2nd instant, and to resume the account of the proceedings of this ship, subsequent to my letter to you of the 1st of March.

I left the Gallinas station on the 2nd March, and proceeded in the first place to land several military officers for the garrison of Cape Coast Castle, where I arrived on the 6th, and on the following morning went on towards the Bight of Benin. Calling at Acra for information, I visited Whydah and Lagos, and successively fell in with the Cygnet and Star which vessels I completed with provisions. I had the satisfaction to find that the division under Commander Layton had recently had considerable success in the capture of slave vessels.

On the 13th I arrived at Princes Island, and took in a supply of water, which is there very good, and 13 tons of coal, which occupied two days. I then proceeded to Fernando Po, where I anchored on the 16th, and speedily experienced the superior advantages of that place for coaling and watering, In three days we took in 300 tons of coal, and 90 tons of water. During my stay at Clarence Cove, I received much useful information from Captain Beacroft the Governor. I had the satisfaction to learn from him, that no Slave Trade had recently been carried on in the Bight of Biafra.

I left Fernando Po on the 19th, and rejoined the cruizers in the Bight of Benin on the 22nd and 23rd. I left the Cygnet, Star and Sealark completely supplied with provisions, and then proceeded to Acra for a supply of cattle for this island. Having on the 25th taken on board 20 head of oxen, I came away, and during my passage to this place fell in with the Ranger which I directed to come here, having reason to believe that I should want her assistance. But the Lily arrived here the same day that I did, (the 2nd instant,) and I was enabled to send away the Ranger on the same evening, with Mr. Gabriel, to Loanda. On the next day, the Lily was sent to the northward, in quest of Lieutenant Stupart, of the Wasp who had been sent to Sierra Leone in a prize, but whose presence I considered indispensable here as a witness in the case of the piracy and murder committed on a prize crew from the Wasp and which I will detail, as fully as I can, in a separate report.

I can now venture to express my thankfulness that through Divine favour the operations in the rivers of Gallinas and Seabar, in the course of February, have had no ill effect on the health of the men employed in the boats. Every precaution was taken at the time, but the unavoidable exposure to pestilential air left me under much anxiety until the several weeks had elapsed during which the coast fever is said to be latent under similar circumstances.

On my arrival here, I was gratified to find that the affairs of the island were, upon the whole, in a satisfactory state.

The public works, under the skilful directions of Captain Frazer, had made a good progress; the catch of turtle had been this season uncommonly abundant, and the island had been well supplied with cattle. My only ground of concern was, as to the state of the water, which, for want of rain, has fallen below what I could consider a safe stock to rest upon; being, by this day's return 560 tons. We are in hopes of rain, but with last year's experience in mind, I consider it my duty to take prompt measures, during the momentary leisure which enables me to give my attention to this matter. Having other business at St. Helena, I have taken on board 100 tons of tanks, which I mean to fill at that island, and to bring back here; and I have taken on board 200 tons of casks in shakes, which I can leave in the commissariat store at St. Helens, and which can be readily set up any time, upon notice being given, and a vessel freighted to bring them on reasonable terms, under the direction of Mr. Gulliver, the Harbour Master, who I believe to be a good and honest officer. By this means, Government will not be exposed to such an infamous act of extortion as was attempted last year in the case of the schooner Eliza Scot. Their Lordships may rest assured, that I will exert myself to place that matter on a proper footing, and to do what is just and necessary, according to their directions.

With that view I shall proceed to St. Helena to-morrow morning, and I expect to return here on the 22nd. By that time I hope to find the witness in the case of the Wasp's prize collected here, and ready to proceed to England in the Rapid which vessel I have sent the Lily to relieve, and to send here forthwith.

I have, &c.

(Signed) W. JONES,

Commodore, and Senior officer commanding.

Richard Drake, Revelation of a Slave Smuggler, 1860.

'Last Tuesday the smallpox began to rage, and we hauled 60 corpses out of the hold.... The sights which I witness may I never look on such again. This is a dreadful trade...... I am growing sicker every day of this business of buying and selling human beings for beasts of burden... On the eighth day [out at sea] I took my round of the half deck, holding a camphor bag in my teeth; for the stench was hideous. The sick and dying were chained together. I saw pregnant women give birth to babies whilst chained to corpses, which our drunken overseers had not removed. The blacks were literally jammed between decks as if in a coffin; and a coffin that dreadful hold became to nearly one half of our cargo before we reached Bahia [in Brazil].

The Gallinas River, Before and After......

The Gallinas river enters the Atlantic in latitude about 7 1/2 °, between Grand Cape Mount and Cape St. Ann, near one hundred miles northwest of Cape Messurado or Monrovia. The name of the river is given to the cluster of slave factories near its mouth. This place possesses no peculiar advantages for any species of commerce, and derives its importance, exclusively, from the establishment of the slave factories there. The land in the vicinity is very low and marshy,the river winds sluggishly through an alluvion of Mangrove marsh, forming innumerable small islands. The bar at its mouth is one of the most dangerous on the coast, being impassable at times in the rainy season. It is located in what is termed the Vey Country, the people of which, are distinguished for their cleanliness, intelligence, and enterprize in trade. How long Gallinas has maintained its importance as a slave mart, we are unable to say, but at the time of our first visit to Liberia in 1831, its reputation was very extended and its influences most deeply felt in the colony. It was estimated that near 10000 slaves were, about that period, annually shipped from this place alone. The business was done, mainly, through the agency of several merchants or factors established there, the principal of which, was Pedro Blanco, a Spaniard. This man's influence was unbounded among the native tribes on that section of the coast, and we fear, at one time extended to members of the colony of considerable respectability. He was a man of education, having the bearing and address of a Spanish Grandee or Don, which was his usual appellation. He lived in a semi-barbarous manner, at once, as a private gentleman and an African prince. He had at one tine a sister residing with him. He maintained several establishments, one on an island near the river's mouth which was his place of business or of trade with foreign vessels, that came to Gallinas to dispose of merchandise; on another island, more remote was his dwelling-house,where he kept his private office, his books, dined, took his siesta, slept, &c.; here, we believe, his sister also resided. On a third, was his seraglio of native wives, each in their several dwellings, after the manner of native chiefs. Independent of all these were his barracoons of slaves, of greater or less extent, as circumstances required. It may readily be supposed that with the wealth accruing from a long and successful prosecution of the slave trade, his power among the natives was equal to that of any despot; and the following incident related to us by one his partners proves that he occasionally exercised it. Having occasion one day to travel on the sea beach some distance from Gallinas, near the island of Sherbro, where he was unknown, he approached the hut of a native with a view of taking rest and refreshment. He asked the owner of the house, who was squatted in the door, to hand him fire to light his cigar. The man bluntly refused, upon which, Blanco drew back, took a carbine from one of his attendants and shot him dead upon the spot.

And About 1850

The advices from Africa, published in our last number, contain the gratifying and important intelligence, that, the long blockade of Gallinas by the British cruisers, has induced the slavers at that place to break up their barracoons, deliver up their slaves to the commodore and to take passage for themselves and effects on board Her Majesty's vessels for Sierra Leone. This is the initiative step to the entire abolition of that traffic on the windward coast; the next, and not less important, is, the purchase of the territory by the Government of Liberia. That the slaves are given up, the barracoons destroyed, the slavers themselves removed and every vestige of this accursed traffic obliterated, avails nothing, unless proper and sure measures are taken to prevent a re-establishment of the business, the moment the coast guard is abandoned; and we doubt not, from the tenor of the advices above referred to, that ere this, either by purchase or conquest, Gallinas and its dependencies are a part and parcel of the commonwealth of Liberia—this measure, only, will ensure it against a reenactment of the scenes of distress and horror which have heretofore rendered that place so infamous.

From James Hall, MD, 'Abolition of the Slave Trade of Gallinas'

http://amistad.mysticseaport.org/library/misc/am.col.gallinas.1.html

HMS Queen Entering Malta Harbour

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Crimean War - The Royal Navy in the Black Sea

landing supplies and troops, landing sailors and marines (blue jackets) to assist the army, principally with gunnery, and in taking off wounded, particularly after the battle of Alma. For the latter, the British Naval Commander, Admiral Dundas, detached his whole fleet, nearly all his surgeons, and 600 seamen and Royal Marines.

The one thing the Navy was not able to do was to directly confront the Russian Navy at sea. They were safely moored in Sebastopol harbour. The one opportunity the Navy had was directly after the Alma Battle, but the allied commanders were afraid to detach the fleet from the land forces, and soon after the Russians sank seven ships across the harbour mouth rendering entry or exit impossible. In doing this the Russians also felt able to release large numbers of guns and gunners for their land forts.

At least Dundas now could feel entirely confident that the Russian fleet was now out of the action, so he concentrated the Navy's efforts in the formation of a Naval brigade to serve ashore in the batteries.

It was directed that each large ship should contribute 200 officers and men, and a contingent of lower-deck or other principal guns; and that the other war vessels should contribute in proportion.

Each ship of the line sent ashore all her Marines, except a few who remained for sentry-duty, and all her best seamen-gunners, together with deck-awnings, spare canvas, spars, and half her ammunition. In all, 2400 seamen, 2000 Royal Marines, and 50 shipwrights, with 65 officers, and about 140 guns, were landed.

On October 15th Dundas met with the other allied Naval commanders to respond to the "urgent request" of the allied land commanders for the co-operation of the fleets in the opening bombardment of Sebastopol.

Dundas was unwilling to give this co-operation. He would gladly enough have met a hostile fleet; but he was strongly of opinion that it was not the business of wooden walls to pit themselves against stone ones.

How right he was.

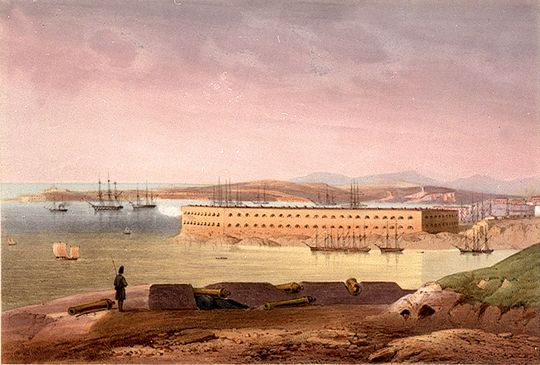

Shown here is a drawing* of the Sebastopol harbour with its many forts, and a detailed image of what appears to be Fort Alexander observed from the Quarantine Fort, as an example of the strength of these defences.

Dundas, mindful of his loss of guns and gunners and aware of the strength of the fortifications, could only at last be persuaded by his fellow commanders.

The plan agreed upon was for the ships to be kept in movement as the gunships at Sveaborg had been; however, the French, at the last moment, insisted on an attack at anchor.......

The disposition of the ships, which had to be lashed to a steamer to manoevre into their 'sitting duck' position, is shown here*.

All that remains to reproduce Admiral Dundas's report to the admiralty on the results of the bombardment*, and to include here the comments of a correspondent present at the bombardment.

'As far as we could judge, it seemed that the amount of damage done to the batteries is literally and truly nothing'

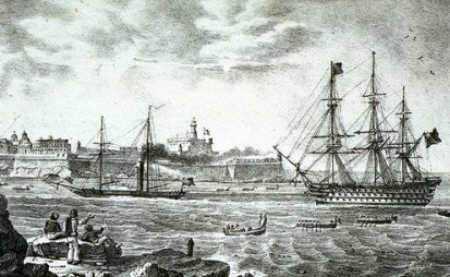

Sebastopol Harbour With Fort Constantine on Left (1) and the Quarantine Fort on the Right (19)

http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/sebast.htm

View of Fort St. Nicholas, Sebastopol, Giving an Illustration of the Size and Strength of the Forts

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Ship Dispositions Before the Bombardment of Sebastopol

http://www.pdavis.nl/Russia2.htm

Vice-Admiral Dundas to Admiralty October 18th 1854

October 18, 1854.

Sir,

1. I BEG you will acquaint the Lords Commissioners

of the Admiralty that the siege batteries

of the Allied Armies opened fire upon the Russian

works south of Sebastapol about half past 6 o'clock

yesterday morning, with great effect, and small

loss.

2. In consequence of the most urgent request of

Lord Raglan and General Canrobert, it was agreed

by the Admirals of the Allied Fleets that the whole

of the ships should assist the land attack by engaging

the sea batteries north and south of the harbour,

on a line across the port, as shown in the

accompanying plan, but various circumstances

rendered a change in the position of the ships

necessary and unavoidable.

3. The Agamemnon, Sanspareil, Sampson, Tribune,

Terrible, Sphinx, and Lynx, and Albion,

London, and Arethusa, towed by the Firebrand,

Niger, and Triton, engaged Fort Constantine and

the batteries to the northward ; while the Queen,

Britannia, Trafalgar, Vengeance, Rodney, Bellerophon,

with Vesuvius, Furious, Retribution,

Highflyer, Spitfire, Spiteful and Cyclops,, lashed

on the port side of the several ships, gradually

took up their positions, as nearly as possible as

marked on the plan.

4. The action lasted from about half-past one

to half-past six, P.M., when being quite dark, the

ships hauled off.

5. The loss, sustained by the Russians, and the

damage done to Fort Constantine and Batteries

cannot, of course, as yet be correctly ascertained.

6. An action of this duration against such formidable

and well armed works, could not be

maintained without serious injury, and I have to

regret the loss of 44 killed and 266 wounded, as

detailed in the accompanying lists. The ships,

masts, yards, and rigging are more or less damaged,

principally by shell and hot shot.

The London Gazette, 5th November 1854

Timothy the Tortoise at Powderham Castle

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Malta Harbour, Thunderer, Howe, Ganges, Vanguard, Wasp & Impregnable

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

The Crew of the Indus March 4th 1860, Bermuda

William Chase, Photographer, http://www.gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/royalnavy/archives.asp?ID=95

HMS Emerald's Ship's Log 28th August 1860

| 28 Aug | Tue | a.m 5:30 Up T Galet masts. Crossed T Galet yards.Pilot came on board Empd receiving troops &c Recd on board 7 officers, 226 non Commd officers and gunners R.A., 23 women & 39 children 8:00 Slipped from mooring buoy and hauled on stern hawser to swing ship Up jib 8:15 Found the ship to have taken the ground on a rock (unknown to the pilot). 5 fms of water all round the ship. Ship touching under the funnel. Down T Galet yrds and masts. Tried to back ship off but without effect. Run all the foremost guns aft. Out all boats. Laid out a hawser on starb[oard] quarter to a buoy astern and one on starb bow to the Halftide Rock. Hove both taut. Got a hawser from a buoy on starb beam to main mast head to prevent ship falling over on her beam ends. Tide falling 11 Low water. Ship healing 4½ ° to port. Water round the ship not less than 4 fms. Bearing when ship was on shore: - Tower of St Annes's Church - S 40 W - Flag staff at Fort Touraille - S 65.30 E Ships head - east Water had left the ship 2ft 8in in aft and 2 ft 0 in forward p.m. 1:30 In all boats 2 Hove on hawsers 2:15 Ship went off into deep water. Slipped stbd, bow hawser - and left them behind, 9 in[ch] hawser, 1 in no., 11 inch, 1 in no. 3:10 Up jib 3:15 Pilot left the ship http://home.planet.nl/~pdavis/Log_Emerald.htm |

Postage Stamps Issued in 2001 Depicting the Grounding of HMS Emerald 28th August 1860

http://home.planet.nl/~pdavis/Stamp.htm

HM Steam Frigate Gorgon (Lying in Hamoaze, Plymouth)

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Commander Wilson of HMS Gorgon Almost Dies Helping Dr Livingstone

From Chapter 11 of 'A Popular Account of Dr Livingstone's Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries'

John Dunsford Jnr's Crimea Medal With Sebastopol Clasp

With Thanks to Margaret Howatson (Craven)

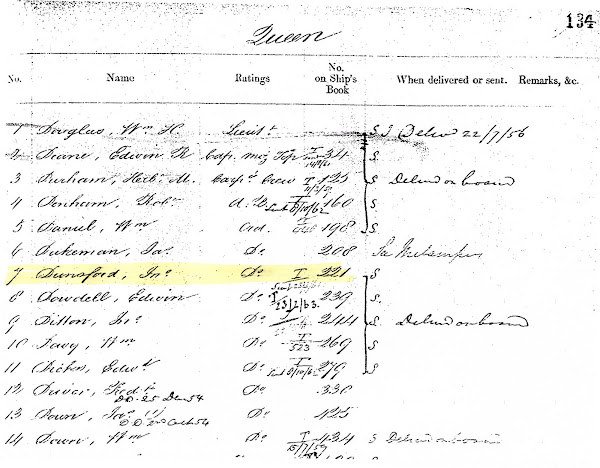

John Dunsford Jnr. On HMS Queen Roll for Crimea Medal With Sebastopol Clasp

John Dunsford Jnr's Memorial Card

With Thanks to Margaret Howatson (Craven)

Adelaide With My Grandfather's Children By Elizabeth Craven Nee Blackmore 1914

+with+mum,+harry,+john,+nita-1.jpg)

My Grandmother, Elizabeth Craven's Headstone in St. Stephen's.

I placed a few pinks at the grave on May 12th 2011, one hundred years after her burial

George Odgers With Kuno in Fore St. About 1930

Aunt Jane Odgers With Emmie in the Backyard of No. 9 Fore St. Around 1920

George and Jane Odgers Virtual Headstone

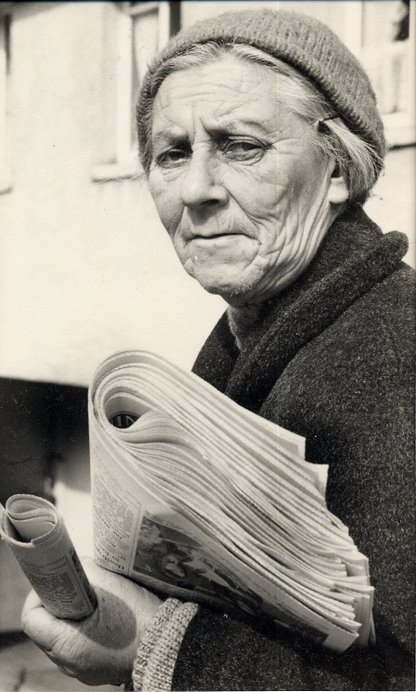

Emmie Odgers Delivering the Papers

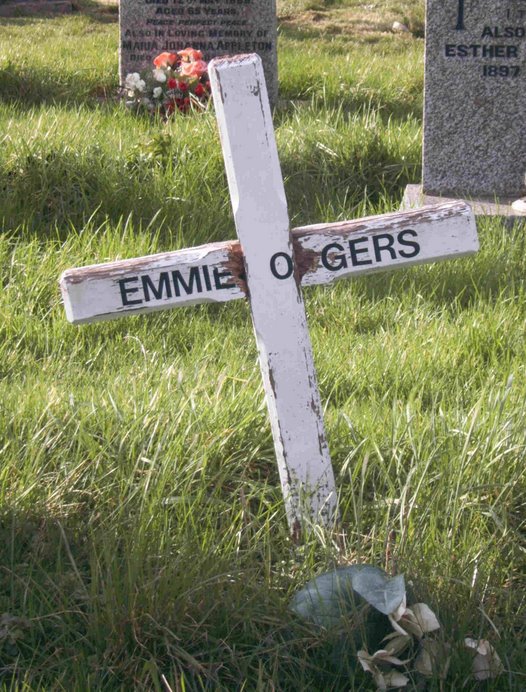

Emma Jane Odgers Grave